Video games take us on journeys through distant and fantastical worlds—whether to save them, destroy them, or sometimes even shape them. But every now and then, instead of letting us burn everything to the ground with a barrage of lasers, games win us over by immersing us in a world that lives, breathes, and evolves… with or without us.

In these games, strict rules fall away, and gameplay is instead dictated by the laws of evolution: what’s well-adapted survives; the rest dies. Of course, we’re talking about simplified evolutionary models here—because at the end of the day, these are still games, not ultra-precise scientific simulators.

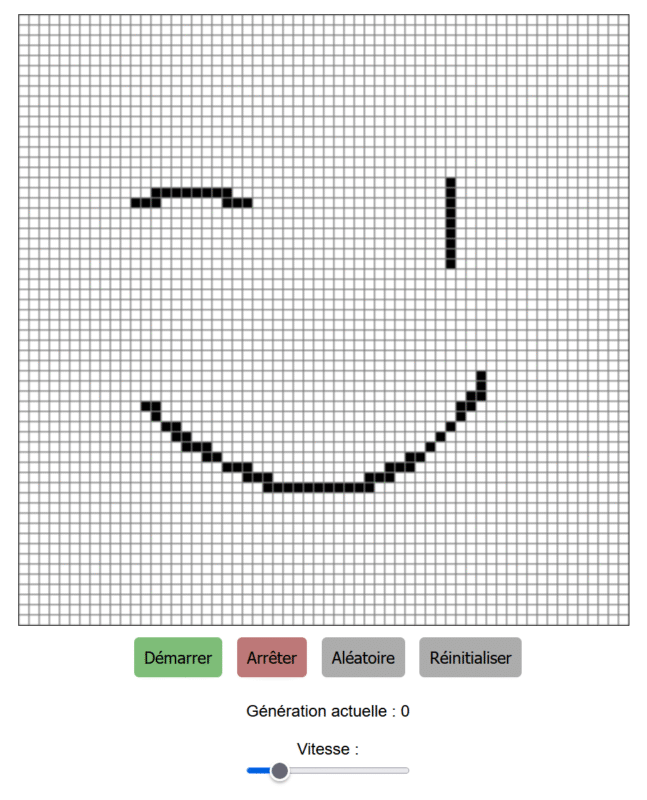

To begin, let’s take a little trip back in time. It’s 1970, and John Conway, then a mathematics professor at the University of Cambridge in the UK, decides to create a cellular automaton (which would later become known as a mathematical simulation game) called the “Game of Life.” In this “zero-player game” (we’ll come back to that in a moment), the rules are quite simple: you have an infinite grid of ‘cells.’ Each cell is either on or off (alive or dead). The game unfolds through ‘generations,’ meaning that the state of the cells at time T directly influences their state at time T+1. Essentially, if a dead cell has exactly three living neighbors, it becomes alive, and a living cell with more than three or fewer than two living neighbors dies (representing isolation or overpopulation).

And there you have it! With just that, we already have a simulation of an ecosystem. Depending on which cells are on or off in the very first generation, you can end up with absolutely mind-blowing results and patterns that repeat themselves and appear for countless “players.” The analogy with microscopic multicellular living organisms is almost too easy to make, and in that sense the game is quite fascinating from a scientific perspective. You can create all sorts of shapes in the first generation and watch them evolve, stagnate, or move around. “Gliders,” “oscillators,” and “guns” are well-known types of patterns, each with its own behavior, and they allow us to illustrate phenomena that mirror those of real life.

But what about the fun factor? Ever since I started talking about the Game of Life, I’ve always put the words “game” and “player” in quotes. Well, even though it’s less interactive than other games, it is indeed a game, with rules and a degree of interactivity, even in the absence of a specific goal (so it’s essentially a sandbox game). At the start of each session, the player draws cells on the grid, deciding which ones are alive and which are not. Then they “start the passage of time,” though they can still modify the cells, bringing them to life or killing them as generations pass. This gives the player an almost godlike power over the little world they’ve just created.

However, even though the player can tweak the grid, they cannot truly control the “future” in an absolute sense : once time is set in motion, the grid evolves autonomously, according to the interactions between the cells.

It’s precisely this semi-automatic nature that makes the Game of Life so fascinating! It relies on a balance between intervention and observation, where the player is both creator and spectator. They shape the initial conditions, set the process in motion, and then watch the dynamics unfold—sometimes predictable, sometimes chaotic. This behavior, which seems random but actually follows very strict rules, closely mirrors real life, and it’s why the game has continued to captivate players, mathematicians, and biologists alike since its creation in 1970.

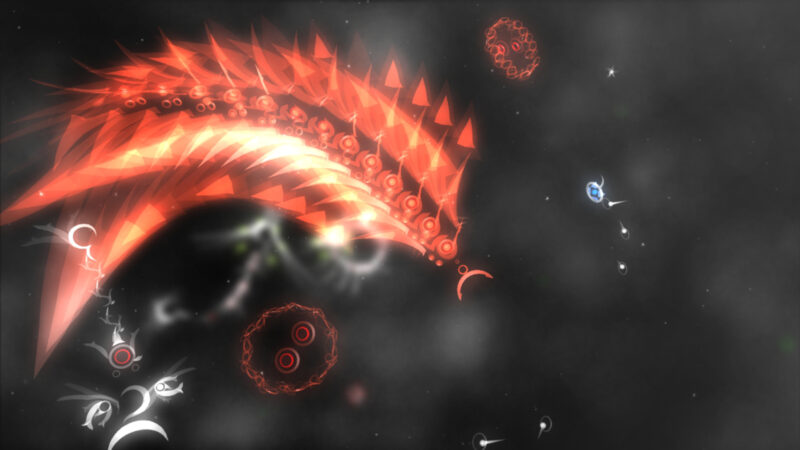

With the technical improvements of the 1980s and ’90s, we were able to go beyond simple pixels on a screen. This made it possible to create games that were more visually appealing, such as flOw, developed by Jenova Chen and Nicholas Clark on Adobe Flash in 2006, and then recreated in 2007 on the PS3 by Thatgamecompany (mostly known for making Journey, and founded by Jenova Chen). In flOw, the player embodies a marine organism, evolving in a world filled with plankton, jellyfish, and increasingly strange sea creatures. In this minimalist game, the player changes and grows as they consume other living beings. Through their choices, the player shapes their avatar throughout the game. What sets flOw apart is its organic approach to gameplay and adaptive difficulty. There are no strict levels or imposed objectives: you dive, explore, and grow. The game naturally adjusts its challenge based on how deep you go. The deeper you descend, the larger and more aggressive the creatures become, while staying near the surface results in slower, more peaceful evolution.

This use of adaptive difficulty (which was still rare at the time) doesn’t rely on simply tweaking enemies or mechanics. Here, it’s the player who chooses their own pace and level of challenge, making each playthrough unique according to their personal style.

The player thus creates their own place in an ecosystem that already exists, already autonomous. With its own food chain, its own biomes (determined by depth and the color of the “water”), and a highly varied bestiary, it almost feels like observing a small universe that doesn’t need us, in which we exist only briefly, and that is actually life (in a nutshell)…

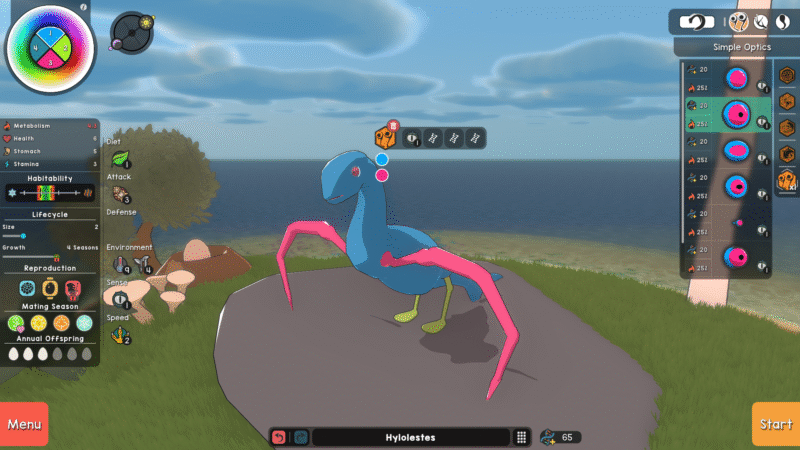

Another game of this type is Adapt. Still in development on the day i’m writing this article, the project was started by Paul Hervé back in 2018, and is already pretty advanced ! In this game, we start by creating a species, adjusting parameters from the simplest to the most complex: stomach size, body shape, fins or/and legs, and much more… The player has access to a very impressive species customization system, and while still being in active development, it already satisfies a number of players, who compare it with Spore, an another “Evolution” game, that had disappointed many at its release due to numerous missing features.

But let’s get back on track, or rather, back to our “creatures.” After creating our species, we start the game and find ourselves on an island.

From here, we can move, feed, fight, reproduce : in short, interact with our environment and our ecosystem. However, this is not a deserted island! You can create a multitude of species: prey, predators, herbivores, carnivores, aquatic or terrestrial beings, and more… and watch them interact with one another: fighting, reproducing, defending, forming alliances…

This game sits somewhere between The Game of Life and flOw. In the first, we were omniscient and could modify the environment at will. In the second, we could only control a single aquatic creature and guide its evolution through our choices. Here, we can both create species and determine their traits, while also controlling individual creatures, giving us a direct influence on the ecosystem.

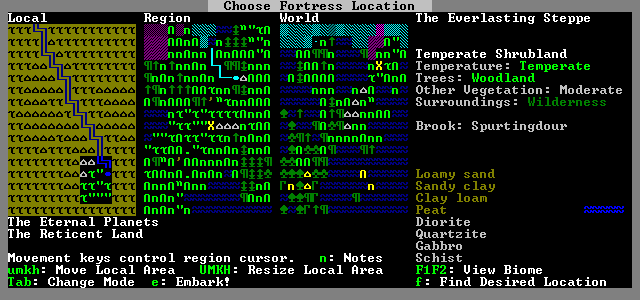

Another game that combines ecosystem building and player-driven evolution is Dwarf Fortress. Still in development like Adapt, it’s designed and developed by Tarn and Zach Adams since 2002. Even though there’s now a paying version (since 2022) on itch.io and Steam featuring better graphics and musics, here we’ll focus on the original version : a free-to-play game using plain ASCII characters. The game can be considered as a sandbox, as it doesn’t give precise objectives : we start by generating a world by tweaking parameters, then we watch our dwarf group evolve, while we give orders and take decisions, in the ultimate goal of creating a “Dwarf Fortress”.

Where Dwarf Fortress differs from Adapt is in the type of ecosystem it depicts. Here, it’s not about genetics or species management. In Dwarf Fortress, the game simulates not just the environment, but also behaviors, social relationships, history, and even the psychology of the dwarves. The possible scenarios are endless, and the billions of stories the game generates could easily fill as many novels.

An accidental flood ? Say goodbye to your sculpted halls and hello to subterranean Atlantis.

An overly enthusiastic mining expedition ? Congratulations, you’ve just unleashed an ancient titan. Good luck with that.

A cat crossing a pool of contaminated mud? Brace yourself for an unstoppable pandemic.

The only problem is that in Dwarf Fortress, even though events can take an unpredictable turn, the player remains the sole conductor of the chaos they themselves set in motion. They observe, plan, and adapt to the disasters they trigger—often unintentionally.

This raises an interesting question: what happens if we take away the player’s role as world creator? We’ve already touched on this idea to some extent with flOw, but let’s go even further: what if the player lost the advantage they usually have in most of these games? What if, instead of controlling their environment, they were subjected to it?

Well Rain World, a metroidvania released in 2017, answers this question with a fascinating brutality. In Rain World, it’s not the world that adapts to you—you must adapt to it in order to survive. You don’t dictate the rules of the game, nor do you truly influence the environment: you are both prey and predator, a mere link in an ecosystem. The world existed before you, and it will continue without you.

In Rain World, you play as a slugcat, a small creature wandering a world ravaged by relentless, devastating rain that marks each “cycle.” Every day is a struggle for survival. You must find food, then rush to shelter, hoping the creatures you encounter along the way aren’t too hungry. Here, there’s no health bar, no reassuring interface. You are alone, and only the law of the strongest prevails.

Charles Darwin once said, “It is not the strongest, the most intelligent, or the best who will survive, but those who adapt the fastest.”

Rain World perfectly embodies this idea, transposing it into a video game world. To date, it stands as the ultimate realization of a living ecosystem simulation in a video game, in my opinion of course.

While The Game of Life, flOw, Spore, Adapt, and Dwarf Fortress are all highly detailed and depict ecosystems with varying degrees of realism, Rain World reminds us of the most important principle when it comes to evolution within an ecosystem : in nature, survival does not depend on stats, strength, or intelligence, but on the ability to continually adapt. By immersing us in a world where every element, from the tiniest predator to the greatest danger—evolves independently of us, it invites reflection not only on our place in its virtual world, but also on our own existence in the real one.

Article by Joseph Rool – 2025

Sources :

General Videos / Indirect References :

Direct references :

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Horton_Conway : Wikipedia article about John Conway (the creator of The Game Of Life)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conway%27s_Game_of_Life : Article about The Game Of Life

https://mathworld.wolfram.com/CellularAutomaton.html : Article about cellular automata

https://conwaylife.com/wiki/Main_Page : TheGameOfLife’s official wiki

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jenova_Chen : Article about Jenova Chen, flOw’s creator and CEO of ThatGameCompany

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thatgamecompany : Article about That Game Company

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Journey_(2012_video_game) : Article about Journey (please play this game !!)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flow_(video_game) : Article about flOw

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dwarf_Fortress : Article about Dwarf Fortress

https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PL-THgg8QnvU5xvhtFe7orgcnfIqFq_qVk&si=V4t0MHpWzEsZI9JB : Playlist on the creation of Dwarf Fortress

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rain_World : Article about Rain World

Leave a comment